Overview

Teaching: 15 min Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is the difference between a model and a machine learning algorithm?

Which of the above is associated with learning?

What are some characteristics of tree-based learning methods?

Objectives

Gain conceptual picture of decision trees, random forests, and tree boosting methods

Develop conceptual picture of support vector machines

Practice evaluating tradeoffs of different ML methods and algorithms

Tree-based ML models

In this section, we will build up from a commonly understood model, a decision tree, to random forests and state of the art gradient tree boosting techniques like XGBoost.

Flowcharts to decision trees

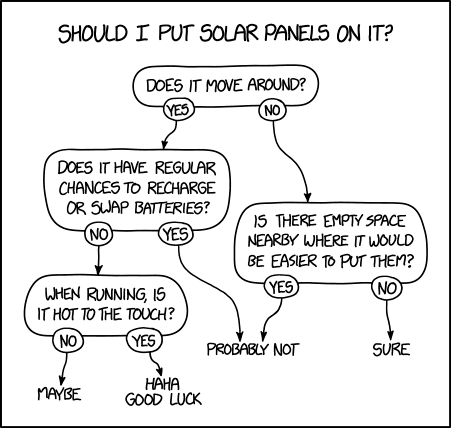

I suspect all of you have seen a flow chart, like this one titled “Solar Panels” from xkcd.

This flowchart can be interpreted as a decision tree. The questions represent covariates (often called “features” in machine learning), while the final leaves represent possible outputs. These outputs are text values right now: “maybe”, “haha good luck”, “probably not”, “sure”. But our proposed solar panel predictive model could be a binary classification task, a multi-class classification task, or a regression task depending on how we add structure to the text.

In the comic’s flowchart, the questions all have binary responses that can be answered with “yes” or “no”. But in your geospatial research, we may have covariates that are numerical. We’ll often see the responses represented using inequalities. More realistic than “Is it hot to the touch?” is a covariate measuring temperature, where the boundary is set to “Operating temperature >= 30^oC”.

So while a decision tree is a model, we haven’t gotten to learning this decision tree for a given dataset. Two algorithms to learn the parameters and covariates for a decision tree include CART (Classification and Regression Trees) and ID3 (Iterative Dichotomiser 3) that are optimized using the Gini index and information gain, respectively.

Conceptually, basic decision tree training algorithms greedily choose the attribute (or feature) that best classifies the training data, repeating this process for each branch. In ID3, we determine the ideal attribute using information gain, or the difference in entropy before and after splitting on that attribute.

Random forests

What do you call a large collective of trees? A forest!

A random forest is comprised of a large number of decision trees. The number of trees used in the ensemble is controlled by a hyperparameter; typically between a few hundred and several thousand. The mode of outputs from the decision trees is used for classification and mean output for regression in most cases.

The benefits of random forests are numerous. While individual decision trees are likely to overfit to the training data, random forests can mitigate that issue. This gives random forests a much higher predictive accuracy than a single tree. Random forests are more robust; slight perturbations in the training dataset do not destabilize the model in the way a single decision tree would.

However, there are some downsides to scaling up to random forests. It is much more computationally expensive to train a random forest. Also, a decision tree is much more interpretable. As evidenced by the xkcd comic from before, flowcharts (and thus, decision trees) are present in popular culture and understood by many. Random forests are not.

Underappreciated is the difference between bagging (or bootstrap aggregating) of tree models and random forests. The difference is slight. Bagging is the process of choosing training examples with replacement from the overall training set, training a decision tree on that subset, and repeating that process. Random forests take this one step forward by also choosing from a random subset of features at each candidate split in the learning process.

Tree boosting methods

Beyond random forests, there are other alterations to tree-based machine learning models that have improved accuracy and other nice properties. We’ll focus on gradient boosting.

Because trees are discrete and add special complications, let’s understand boosting conceptually using generic functions and regression. Unlike bagging methods, like what we see in random forests, boosting methods can not be built in parallel. Boosting methods build trees one at a time; each new tree helping to correct errors from the previously trained tree.

General tree boosting algorithms, like AdaBoost, correct these errors by increasing the weight of observations that were previously misclassified. Gradient boosting corrects these errors by targeting large residuals of the previous model iteration.

Our model’s residuals, or difference between the true label and our model’s output, can provide knowledge about improving our model. We then create an improved model $F_{m+1}(x) = F_m(x) + h(x)$ where h is fit to these residuals, $y - F_m(x)$. We continue this process for some number $m$ of trees.

One blog resource comparing random forests to gradient boosting is here.

A very popular implementation of gradient boosting is XGBoost by Tianqi Chen while he was a grad student here at the University of Washington. His particular contribution was a novel sparsity-aware algorithm, weighted quantile sketch for approximate trees, and other insights that speed up performance considerably. Read the paper on arxiv here.

Support vector machines (SVMs)

Support vector machines (SVMs) are a particular machine learning technique in the broader group of kernel based methods, just as random forests are one of many tree based methods. Unlike the last category, this tutorial will be focusing on a single kernel-based method.

Key Points

supervised learning, flowcharts, decision trees, random forests, boosting, gradient boosting, tensor, SVM